Birthday essays for Dr. Rosan Daido Yoshida

September 9, 2024

Happy birthday!

The Mitras have compiled these birthday greetings and reflections in celebration of our friendship and meetings. Please enjoy the day!

With deep respect in life, light, liberation, and love,

Ekan Mike Currier

Erin Daiho Erin Davis

Gento David Dickey

Myoku Michael Lavin

Rofu Roberta Lavin

Garyo Daiho Gertraud Wild

.

.

Kindness is the mark of a person who has uncoupled the fetters of karma, and lives a wholesome happy life without the distractions of self-centered focus. I am grateful for the kindness shown to me by you, Sensei, and the practice of zazen, which helps me be a kinder person. The gift of zazen has made, and continues to make a big difference in my life … it is the every-day refuge I go to – to reset my attitude and remember my true Self.

Thank you, and may every day be a ‘Happy Birth Day’! With Deep Bows,

Ekan

How has zazen and the study of Buddhism affected my life? As a conservation biologist my job is to protect the 10,000 species and the habitats they depend upon. There are more than 10,000 species, if you consider all the micro-organisms, algae, fungi, invertebrates, vascular plants, mosses, lichens and on (10,000 is a metaphorical number!). I have learned through steady practice to ‘slow down’, focus, and breath, allowing the ‘10,000 things’ to reveal themselves. There is no end to the reveal or what form the reveal takes! Part of my transition from ‘horticulturalist’ to ‘botanist’ to ‘conservation biologist’ was inspired by the deep urge for nature to guide me (not the other way around). The gentle (and sometimes painful) practice of zazen allows for deep immersion in the natural world, blending pure awareness with understanding and knowledge. Mudra by mudra deepening & disappearing …….

Resting in the soft bed of biodiversity;

Laying serene in glade grasses and woodland leaves; Breathing in……..

Wild Dittany, Bergamont and Calamint; Breathing out…..

Reflections on the Missouri Zen Center

I first attended a Missouri Zen Center (MZC) Beginner’s Night session in 2008. Over time I came to participate in MZC activities fairly regularly – sittings and sesshins, work days and board meetings, study groups and sewing practice – until I moved to Washington State in 2013. Writing now in the summer of 2024, I can reflect on how those five years continue to influence the direction of my life.

At the beginning I was drawn back again and again by the work days. I learned later that samu is an important element in Zen practice, but because I lived in an apartment at the time, yard clean up at MZC mostly represented for me a cherished opportunity to work outside. I especially enjoyed working with the sangha, in community. We would start with zazen, which set the tone for quiet, focused activity. After working together for a few hours, we would finish with a potluck and good conversation. After what might have been a stressful work week, those days pulling weeds or planting flowers made me feel refreshed.

And then there are Dr. Yoshida’s teachings. I had read about Buddhism here and there, but learning how its history, philosophy, culture, and practice fit together, and are embodied in one’s way of living, was very interesting to me. I’m deeply grateful for the opportunity I’ve had to work on various editing projects, because they have helped me to see those things from perspectives I may never have encountered otherwise. Dr. Yoshida was a child of war in Japan; I’ve been witness to how he has dedicated his life to the teaching of peace. Two texts in particular – the Metta Sutta and the Fukanzazengi – address that topic directly and indirectly, and I hope to open the gate of peace through them with Dr. Yoshida’s help.

Finally, I will always have this practice of zazen. It’s the core, the very center of practice at MZC. After Dr. Yoshida retired from teaching in Japan and moved permanently to the US, he has always attended the zazen sessions, morning and evening, six days (sometimes seven days) a week. Steady, consistent practice, unwavering. It can be a challenge for beginners like myself to cultivate a practice that is only dimly understood, if at all. At first an element of faith, born of and strengthened by such consistency among generations of practitioners, encourages one along. Later, still dimly understood, if at all, the practice of zazen feels like steady cultivation.

The MZC has seen so many people pass through its doors through the years, all of us guests for a little while. We can all reflect on how we carry that meeting in our lives.

Erin Daiho Erin Davis

A Tribute to Dr. Osamu Yoshida (Rev. Rosan Daido)

I don’t remember the exact date, but it was sometime around 1982, moved by an interest stirred by reading people like Alan Watts, and based on a referral from a friend, I first began sitting with Dr. Osamu Yoshida at a place called the St. Louis Yoga Center. I was a little bit apprehensive, and I didn’t know what to expect, but I found the place and entered. I immediately felt welcomed, and as the morning progressed and I had my first experience of upright seated Zen meditation, I felt I had found a home. I had this strong sense that I was in the right place.

Right away I was struck by both the depth and the gentleness of his teaching. There was a naturalness to be found in sitting on the cushion. I felt grounded, sitting firmly on the earth. I felt a commitment to the practice right away, but even with that being the case, I was pleasantly surprised when Yoshida Sensei invited me to be in the first group from the Missouri Zen center to participate in a lay ordination, since I had been attending for just over a year. The tedious effort involved in sewing my rakusu, and the solemnity of the ceremony officiated by Katagiri Roshi helped to deepen that commitment.

Through the patient way in which he encouraged each of us to see the truth of the Dharma for ourselves, I began to build a foundation for a deepening practice. I especially remember the way in which he would translate and share with us essays from the Shōbōgenzō and through his interpretation, illuminate the teachings of Dogen. Even though Dogen’s writings seemed incomprehensible, I could sense on some level that they expressed a deep truth. I began to understand that enlightenment was not a destination but a way of living. Perhaps the most helpful of all those writings to me is the Fukanzazengi. In fact, in my current place of practice, we recite it during every Wednesday evening meeting, and as part of our midday service during sesshin. Through Sensei, I was able to acquire vocabulary of Zen, not just the terminology derived from Japanese and even Sanskrit language, but a vocabulary for living, for seeing the deeper truth in the meaning of everyday experience.

I was even more grateful when he asked me to assume a leadership role during a year in which he had to return to Japan, shortly after the death of Katagiri Roshi. His faith in me deepened my willingness to persevere, to be an example to others. Working together, we managed to maintain the sangha until his return.

It is difficult to find the words to express my gratitude for his example. The realization that one must have a teacher whose way of life is rooted in the practice of the Buddha Dharma was the reason for seeking out a teacher when I arrived where I now live in South Carolina. It was my good fortune in fact to find such a teacher here and continue my practice. It was sometime after I arrived here when I first met Reverend Master Rokuzan, and I knew immediately that his teaching was also rooted deeply in the

Buddha Dharma, but I would not have known this if not for the excellent foundation

given to me by the beneficent offerings of Dr. Yoshida.

So how do I express my thanks and deep gratitude generated by four decades of Zen practice? How do I thank the masterful teacher who so generously planted the seed of practice? I think the answer lies in cultivating transparency of the self, minimizing ego, and allowing that same teaching to flow through me as an example to others. That is the way of life that I aspire to today, and I have Reverend Master Yoshida to directly thank for that, as I continue to cultivate the mind that seeks the way.

Gentō (Dave Dickey)

……………………….

What Rosan means to me begins on a warm Spring Day in 2016 when Roberta and I came to the Missouri Zen Center for the first time. The first evening we attended, I believe Jimu was still active at the centre, Jimu is tall man and watching him standing next to Rosan created a disparity of heights that amused me.

Whatever Rosan lacked in heights he had in presence. He had bearing and intellect that made him unmistakable. He occupied a zafu like a mountain with superior posture. When he spoke in accented English, he one could sense his intelligence.

And so I was unsurprised when I learnt he had left Japan to come to the United States to take a PhD in East Asian Studies at Columbia University. His time there resulted in an original monograph titled No Self: A New Systematic Interpretation of Buddhism.

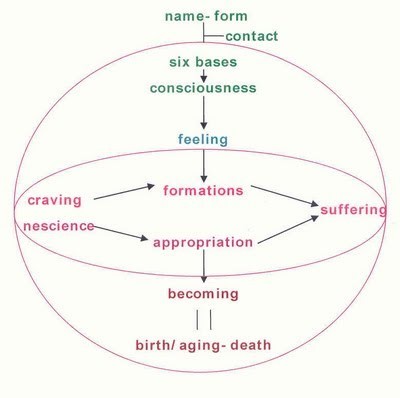

The book showed the breadth of Rosan’s knowledge and his willingness to travel along his own path towards a better understanding of the Buddha and his doctrines. For example, Rosan argued for a novel understanding of the complicated doctrine of Dependent Origination. Traditional Buddhist texts present the doctrine of dependent origination as if it were a sequence. For didactic purposes, the monkish tradition eased a young practioner’s learning; however, Rosan believes the traditional teaching of the doctrine isn’t describing an actual linear sequence of experiences, but “a linear expression of a structural form.”

.

.

Rosan’s structural pictures offers practitioners away of comprehending how suffering emerges and how a practitioner might go about averting it. And it is a picture consistent with the Buddha’s teaching. Anyway, if anybody takes the trouble to look at Rosan’s circle and its organization, whilst also looking up its terms, you will earn a great deal more each time you do so. Or so I predict.

Some of this shows in Rosan’s willingness to dispense with standard translations in an effort to give readers a right understanding of what the Buddha had to say. As Rosan often reminds us, the Buddha did not write anything. Instead, we have works that Buddhist traditions say Ananda memorized to memorialise the teachings that are translated after the ancient world got the gift of writing. Further, monks in time collated the writings to aid teaching.

Rosan stands out from the first two teachers I had—John Grimes and Colin Gipson—at the San Antonio Zen Cetner. Being from Japan, he came from a background with a longer, richer Buddhist culture than exists in the Americas. His education in Japan equipped him with a matchless understanding of both Buddhist, most especially Zen Buddhist practice, but an education that further his ability to see the implications for ordinary life that Buddhism has.

I think it is fair to say that Rosan believes with all his heart that Engaged Buddhism is Buddhism. On issues of the environment, he and Thich Nhat Hanh travel the same path. I’ll admit activism of Rosan doesn’t come naturally to me. If I have an activist bone in my body, I have yet to discover it. Still, I do listen. I appreciate a man of Rosan’s calibre who is willing to follow an argument to its conclusions. He has, though, never managed to pull me away from live classical music and live opera, as much as I like clear reasoning.

Because of Rosan, I was accepted for Jukai. I still have vivid memories of the ceremony. I was glad to do it, but my back was not so grateful. I think that commitment to using the precepts, one of the vows of ordination, has made my presence easier for Roberta and friends to bear, though I also got benefits. Without Rosan’s kind example, I doubt I’d have ever taken lay ordination. I’d have been content to muddle along without any form of ordination.

If you’ve known Rosan any length of time, you know he is generous. He is a gracious giver. I have had gifts of books he has translated or written from him. I have had gifts of chocolate from him. If you visit him, you can count on superb tea. He also knows how to cook rice. Above, he does not cling to what he has. I discern no greed in him.

After Roberta and I moved from Saint Louis, we maintained a connection to the Center.

Since we’ve been in Albuquerque, we have joined a circle of friends that Rosan created

to allow persons that time had scattered to form a sangha or community that assembles on Saturday evenings to sit together and to hear Rosan give a dharma talk. The talks offer anybody attending the chance to ask Rosan questions that create deeper and broader knowledge of the theory and practice of Buddhism. I count myself lucky to have this circle of friends. It is yet one more thing I owe Rosan.

Finding a Teacher

The path to finding a teacher with whom I could form a bond of trust and respect has

been special and long. Reflecting on my introduction to the origins of Zen Buddhism as an undergraduate student I found Eastern region fascinating and different from my very limited childhood introduction to Christianity by my mother. My fascination resulted in an unintentional minor in religious studies. Studying Zen Buddhism in a couple of college courses provided a bracketed understanding on the origin and history of Zen Buddhism. The courses were designed to provide information on the transmission of insight from the Buddha to his disciples and not to provide students true insight. Without practice, all understanding was superficial and knowledge brought no freedom from desires.

A college professor is not the same as a Zen Master

(teacher). Many texts refer to the teacher as master.

While there seems to be differences in the terminology in text, I always hear it as master teacher. The Zen master teacher is one that can see in the student what she may not see in herself.

Historically, the teacher’s authority was based on an unbroken lineage tracing back to Siddhartha Gautama himself, which helped authenticate a teacher’s teachings and practices. Famous teachers from Bodhidharma to Huineng have been crucial in shaping Zen practice. Their emphasis on direct experience and personal realization over scholarly learning redefined spiritual education. Through my study with at the Missouri Zen Center in the lineage of Dainin Katagiri to Rosan Osamu Yoshida I have found a joyful medium between scholarly exploration and practice.

The work of Dogen and Eisai clarified the teacher’s role not only as a master teacher but as a spiritual ancestor who adapts the teachings to the cultural context of the time. This adaptability highlights how teachers have historically tailored Zen principles to meet the evolving needs of communities, ensuring that practice is relevant. In our time one such emphasis is the work on socially engaged Buddhism whether that be related to environmental consciousness or a world without war.

The significance of finding a teacher. At the heart of Zen is the role of the teacher in Dharma transmission, the passing of doctrinal authority from teacher to student, which is less about the literal transfer of knowledge and more about confirming the student’s insight into the nature of reality as it is taught. This process seems crucial as it perpetuates the Zen lineage and ensures the authenticity of teachings through

generations. One only needs examine early Christian teachings to those of modern

progressive or evangelical wings to know why an authoritative source is important.

Historically teachers have used such methods as koans (riddles that defy logical reasoning and seem very oriented toward eras, language, and cultures and leave me wondering how they are helpful in reaching enlightenment) that may foster enlightenment. Of course, the purpose is to challenge the dualistic way of thinking in our ordinary consciousness, though clearly it is not the only means to encounter our dualistic leanings and I am grateful, it has not been an area of emphasis at the Missouri Zen Center.

The practical importance of Zen practice to me. In our Sangha the Zen teacher’s role has included guidance on seated meditation, sesshin, and daily practice, with an emphasis on keeping the precepts. Like other modern Zen teachers Dr. Rosan Yoshida is pivotal in stressing the application of Zen principles in everyday life, social engagement, and an ethical approach to life.

Teaching often focuses on how to maintain presence and awareness throughout daily activities, helping us to cultivate a state of continuous practice that carries with us off the zafu. While it may or may not be the intent it provides guidance to help direct us through the challenges of everyday life, using traditional Zen teachings to address the issues of today and to grow as human beings engaged with the world.

Throughout history, the Zen teacher has been a cornerstone of spiritual education in Zen Buddhism, embodying the transmission of truth and wisdom. From the ancient monasteries of China to our online Zen sangha, Rosan has continually adapted the teachings to meet the needs of his students, ensuring the relevance to our practice. The enduring significance of our teacher is not only in the role he fulfills but in the profound impact he has on individual lives, guiding students toward enlightenment and a deeper understanding of ourselves and our place in the world.

.

My personal expression of gratitude and admiration. I am deeply grateful for the

guidance and wisdom imparted by my Zen teacher, under whom I received Jukai, and

formal joined our Zen Buddhist community. His patient guidance and compassionate presence have been instrumental in shaping my understanding of Zen practice and nurturing my spiritual growth.

Beyond the teachings within our virtual monastery walls, my admiration for socially engaged Buddhism has been fostered by the example set forth by my teacher (Rosan).

Socially engaged Buddhism, a movement that advocates for applying Buddhist principles to address social, political, and environmental issues, resonates deeply with me. Witnessing Rosan’s commitment to compassion in action, whether through

community outreach initiatives, environmental stewardship efforts, or social justice advocacy, has inspired me to integrate mindfulness and compassion into every aspect of my life, extending beyond the zafu into the world around me.

In embodying the principles of Socially Engaged Buddhism, Rosan exemplifies the timeless relevance of Zen teachings in addressing the challenges of our time. His dedication to service and his unwavering commitment to alleviating suffering in all sentient beings serves as inspiration, reminding me of the profound impact one individual can have in creating positive change in the world.

As I continue on my journey of self-discovery and awakening, I carry with me the profound lessons learned from Rosan – my Zen teacher – and the profound respect and gratitude for his instrumental presence in my life. One day I hope to teach others in his lineage.

.

Missouri Zen Center

Twenty-five years ago, when I moved to St. Louis, I looked in the phone book in search of a Zen Center. I found the Missouri Zen Center on Spring Avenue in Webster Groves. For years, I was reading the books of the mystic Meister Eckehart and was intrigued by his suggestion to empty the mind – but how can I do that? I did not have any idea or tool to work with my mind. This changed when I started practicing meditation at the center. Finally, there was a way to walk, a finger pointing to the moon.

Meditation and the teachings of Rosan became crucial in my life. Rosan challenged my mind. When he first talked about the concept of No Self, I was totally lost. It contradicted the concept of Higher Self according to C.G.Jung that I was familiar with. When I asked Rosan about dreams, he did not find them important. This confused me even more. Dreams were crucial for me.

Regardless of this tension, I continued practicing and received Jukai or lay ordination together with my Dharma brother Jimu in 2001. Rosan gave me the Dharma name Garyo, meaning gracefully cool. In addition to the precepts I vowed to follow, my name pointed me to a direction I wanted to go – the direction towards equanimity.

My physical time in the Missouri Zen center did not last long. In 2005, I permanently moved to Vienna, Austria. However, I never lost contact with Rosan. Back in Europe, I started to walk long pilgrimages and Rosan allowed me to share my experiences on his blog. At one point, I mentioned the 88-temple pilgrimage in Shikoku and that I did not dare to walk it alone. His encouraging words helped me to overcome my fears. I had an amazing experience. He also suggested visiting the Zen temple Zuioji. I was allowed to practice with the monks for one week. At this time, Rosan’s teacher, Tsugen Narasaki Roshi, was still alive and I could see him as the Living Dharma, a name the monks used to describe him.

Over time, I got a feeling of the meaning of No Self and also could integrate my understanding of dreams with the teachings of Zen. Still, Rosan’s sharp sword of wisdom was sometimes shattering my understanding of a koan or symbolic meaning. Confused at the beginning, his words always revealed the truth. Practicing meditation and No Self became a guiding force. On December 8, 2023, I was ordained as a Zen priest, together with Jimyo. The simplicity and the depth of this ceremony was beautiful. I know that I want to walk the path of service, keep the three treasures of Buddha, Dharma, Sangha in my heart and do my best to be a disciple of Buddha. I do not know where the path will take me. However, I will always be grateful that Rosan pointed the way ever since I met him. It is the way of limitless life, love, liberation and light.

.

.

.