Nakahechi route

Yuko and Shigeo drove seven hours from Eihei-ji to Tanabe, a town on the western coast of the Kii peninsular. It is the starting point of the most popular pilgrimage route of the Komano Kodo, the Nakahechi route (about 90km including a boat ride). The imperial family and nobility coming from Kyoto used the Nakahechi route to visit the three most important shrines located in Kumano – Kumano Hongu Taisha, Kumano Nachi Taisha and Kumano Hayatama Taisha. Starting in the 10th century, this difficult journey connected with nature worship was filled with strict spiritual trainings in order to purify body and mind. Sometimes, up to 800 people walked this path with the imperial family. People considered the Kumano area as the abode of Gods where deities (kamis) descended and resided and the place where the spirits of the dead congregated on the mountain tops.

Kumano is also associated with the mythological foundation of Japan (recorded in the Records of Ancient matters, 711-712 CE). According to these records, Jimmu, the first emperor of Japan and direct descendent of the sun goddess Amaterasu, was guided by a three-legged crow (Yatagarasu) through the wilderness of Kumano and won the war against his adversary. This was the beginning of the nation Japan.

.

.

.

.

Web of Cedar roots

on the ancient path

Kumano Kodo

.

.

In Tanabe (called Gateway to Kumano), we were joined by Hiroko-san, a good friend of Yuko and Shigeo. When we were ready to check out from our hotel in Tanabe on Sunday morning, I realized that I had a health problem – a bladder infection. It started a day before, but this morning, I could not ignore it anymore – I had to go to the doctor! However, going to a doctor would have caused us to lose one day of hiking. I decided to treat it myself by drinking lots of water mixed with a bit of baking soda (I got it from the hotel) and wait. It turned out to be the best decision I could make. Walking thousands of steps in beautiful nature and drinking lots of water was not a total cure, but a way to healing. Although my decision was not based on the ancient belief that walking ” in this sacred paradise on earth” brings healing and relief from suffering, my bladder problems became less urgent.

.

.

.

.

Like the lake below

may you be quiet and calm

my busy bladder

.

.

We started our hike at the Takajiri-oji, the entrance to the Kumano mountains. An Oji is a subsidiary shrine to the Grand shrines and once were located every two km as a place of worship and rest. Many of them disappeared. The Takajiri-oji is located beside the Tonda river, in former times a very dangerous river crossing where many pilgrims died. Severe cold-water rituals were performed with dances, sutra chanting, prayers, sumo wrestling and poetry recited. Many big halls, bathhouses and lodges for pilgrims stood there one time. Nothing is left except the oji. A modern visitor center is located on the other side of the river.

.

.

.

.

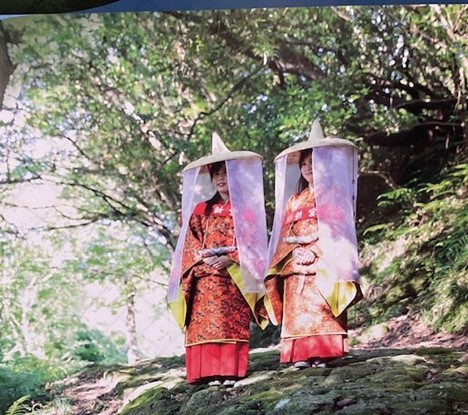

A photo in the visitor center depicting two female pilgrims dressed in typical pilgrims’ outfits: the kimono and a straw hat with veil. The hat not only protected the pilgrims from insects but also had a spiritual significance, symbolizing a protected space from outside impurities.

..

.

.

.

Torii to the Takajiri-oji. When entering through the torii, one has to bow. The area is considered sacred.

.

.

.

.

Purifying hands and mouth is important before approaching the shrine

.

.

.

.

The ritual at the shrine is performed in the following way: first by ringing the bell, then two bows, then two times clapping, followed by a short prayer. Before leaving the shrine, one has to bow again.

.

.

.

.

A small wooden house on a pole holds the stamp for the pilgrim’s book

.

.

The pilgrim’s path immediately leads into the forest and up the mountain with steep natural stairs of rock and roots.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Constantly, the wind blew hair in my face. This caused me to write a haiku

.

.

Wind in the tree tops

also blows hair in my face –

we are connected

.

.

.

.

.

The path is well marked

.

.

.

.

Each step at a time

on the narrow mountain path –

old leaves on the ground

.

A tree embracing a rock with its roots – so tender!

After hiking for a while, we came to a very interesting rock formation called “Chichi-iwa rock”, connected with a legend. One time, the legend says, a wife took shelter in its cave in order to give birth to a baby. She continued the pilgrimage and left the baby in the cave. The baby survived because a wolf fed the baby with milk dripping down the rock. When the couple returned from the pilgrimage, they found their baby and took it home. Therefore, the rock is called “milk rock”.

Yuko and I climbed through the very narrow rock passage to the other side. It is like passing through a womb and being reborn.

.

.

.

.

.

It is impossible to crawl through this narrow hole with a bag-pack

/

/

/

.

.

Jizos, protectors of wanderers and children, with bibs

When we reached the top of the mountain, the path followed a beautiful mountain ridge lined by tall cedar trees.

.

.

.

.

.

Our goal of the day was Takahara, a beautiful little mountain village with a spectacular view. The fields below are rice fields.

.

.

.

You can see layered rice terraces which require a sophisticated system of water control. In former times, the cultivation of rice was considered a sacred act. Many religious symbols use rice plants for rituals in Japan. Rice is often offered to deities in shrines and at home and the rice straw is used for the shimenawa, a rope made out of rice to indicated a sacred area.

In Takahra stands also the oldest shrine of the Nakahechi route, the Takahara-Kumano -jinja (14th century). This sacred place is surrounded by powerful, nearly 1000 year old camphor trees.

.

.

.

.

Takahara jinja with 1000-year-old camphor tree to the right

Near the jinja also stands a pillar called Koshinto (unfortunately, I do not have a photo). An ancient believe is connected with it: Every 60 day is Koshin day. During the night of this day, three worms called Sanshi would escape the body and ascend to the Gods where they would report all the sins of this person – this would lead to a shorter life span. In order to prevent this to happen, the people did not sleep all night.

.

.

.