Time in the Soto Zen temple Eihei-ji

When planning the pilgrimage Kumano Kodo, Ancient Path, Yuko asked me: “What do you want to see and experience in addition to Kumano Kodo?” Immediately, Eihei-ji came into my mind. Eihei-ji, (temple of eternal peace) was founded by Eihei Dogen in the 13th century and is one of the two head temples of Soto Zen. As a practitioner of Zen meditation, I was aware of this temple but never thought that I ever would have the opportunity to visit it. Eihei-ji is located northwest of Tokyo, the Kumano area is in the south. Yuko and Shigeo had to do a big detour – it was incredibly generous of them to drive so many more hours to take me there.

Eihei-ji is nestled in a valley surrounded by huge cedar and maple trees. Deep green moss is covering the ground and rocks, radiating peace and serenity. It covers an area of 330, 000 sq. meters (0,13sq. miles) and is used as a training monastery for monks in residence since Dogen founded the temple in 1244.

.

.

.

.

Scenery on the way up to the entrance gate

.

One of 70 buildings of Eihei-ji Zen village

.

.

In front of the entrance gate a little pond with a Bodhisattva sitting on a leave and a frog in the water

.

A clear river flows through the valley

.

.

Entrance gate to the visitor building

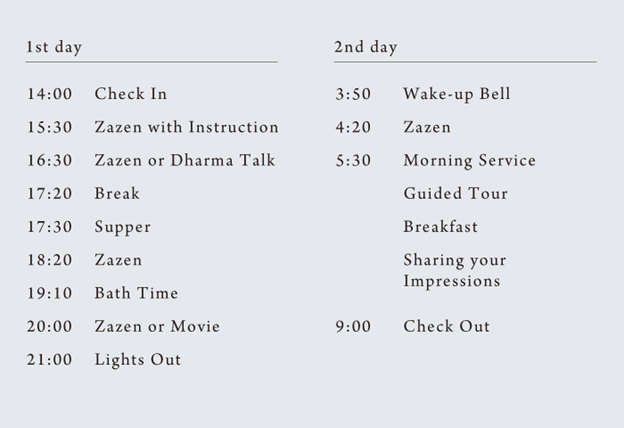

At 2 pm, I walked through the gate leading to the reception desk for visitors, presented my application paper and got a locker for my shoes. Everyone had to wear reddish-brown slippers in the temple, which was not easy for me to walk in. A monk handed me a paper describing the schedule of my two days stay.

Schedule

.

In excellent English, another monk was leading us through the temple complex and explained the different buildings on the map. It was interesting for me that the painter needed more than 4 years to finish it.

.

.

.

.

The building he is pointing to is the four-story modern building reserved for people who want to practice zazen (sitting meditation). One can sign up for a short period of time for specific programs offered. You need to apply for permission to attend.

The architectural design of the temple complex was brought back by Dogen from China. While only 23 years old, he went to China to deepen his practice and reached enlightenment. When returning to Japan, he put all his effort into teaching the way of awakening. The temple and the layout of the buildings is part of his teaching plan. It is constructed like Buddha’s body or any human body. The highest building called Hatto, Dharma Hall, is the place where sutras are chanted and corresponds with the head. However, the most important building is the Butsuden, the Buddha hall underneath the Hatto. It refers to the heart. Below the Butsuden to the left and right are the Sodo (where the monks meditate, eat and sleep) with toilets and Daikuin, the kitchen, and Yokushitsu, bath (the communal hot baths are very important). Dogen’s remains (he died at the age of 53) are kept in the founder’s hall beside the Hatto. I found it interesting that, like Kobo Daishi in Koyasan (founder of Shingo Buddhism), he gets food served three times a day.

.

.

.

Corridors connecting the buildings are like arteries of the heart (photo from the internet). Each building is connected by roofed corridors or a long distance of roofed stairways.

.

.

The Sanmon gate (main gate), built in the traditional Japanese wood-joining techniques, (not using a single nail) was built in 1749.

.

.

The bell tower, Shoro

.

.

Butsuden, Buddha Hall (photo from the internet)

.

.

.

This monk, who I erased his face to respect his identity, is ready to hit the cloud shaped bell announcing breakfast. He seemed a bit confused when standing on the little pedestal, holding the instruction papers. Our tour guide saw that and shouted that it was too early to hit the umpan. Obviously, he was a newcomer. Helping and supporting each other in the practice is a very important characteristic in a Zen monastery. Zen temples are compared to forests where monks practice together in harmony like trees and grasses. I could experience that in Zuioji 8 years ago, with Daikai-san showing me the way how to be in the in harmony with the community of practitioners.

.

.

Hatto, Dharma Hall

The program I was admitted to is called Sanzen, designed for foreigners already knowing about meditation. We were 12 participants from all over the world and stayed in a four- story building attached to the main buildings of the temple, but separate. I was assigned to sleep in a tatami room with two young women, one from Lithuania and the other from Hongkong. Everybody spoke English, so we could communicate with no problem.

We had several forty minute long sitting meditation sessions (zazen) with 10 minutes of walking meditation afterwards. Silently, without hearing any steps, a monk went around to adjust the posture. We could also ask to be hit by a kyosaku (flat, long stick) on the shoulder, beside the neck – if we wanted to. It relaxes the shoulder and vitalizes the entire body. It feels really good – I knew it from past retreats (many western temples stopped doing it because of negative reactions from western practitioners). I asked for it by bowing and the folding my hands in a position called gassho and was grateful for this experience.

The hot bath was wonderful and I was so glad that I knew the Japanese way of bathing and could share my knowledge with the other women.

Like in Zuioji, the time to wake up was announced by a monk running with a bell in the different corridors where people are sleeping. The wake up bell was supposed to wake us up at 3:50 am. This gave us time to wash, brush our teeth, prepare the room for leaving at 9 am and pack. I was already half awake at 3:30 am and waited for the bell to ring, but there was nothing. Interesting, I thought, how time feels different, sometimes passing so slowly! Suddenly, I heard the happy ring and looked at my phone. It was 4:20 am! The monk had overslept! Our meditation time was shortened in order to reach the sutra chanting in the hatto. It was to me an incredible teaching of accepting mistakes, becoming aware that nothing is really perfect and all we can do is to do our best. In Zuioji, the general greeting translated into English is ” thank you for your effort!”

At the end of my stay in Eihei-ji, I picked up the document called Goshuin, certifying that I had visited the temple. I brought my own book I bought 8 years ago in Koyasan with stamps and calligraphy from other temples already recorded in it. It felt good to have a continuation of my journeys.

Also, I learned that Daikai-san, the monk who cared for me when I lived and meditated with the monks eight years ago, became a teacher for Eihei-ji and visits the temple on a regular basis. He is now an abbot of his own temple called Chokokuji.

.

.

.

Daikai-san and I at the end of my stay in Zuioji

.

.

.